#13 PART.II.thought — Desire and Thought in Practice

The Goal in Architecture PART.II.0.2 Desire

Desire is for me related to the image of our future that the Jetsons cartoon portrays where technology had made everyone luxury dwellers. This future was promised to me more than once during my school days. One would desire that. There is no land nor a tree to be seen, they live up in the sky, and the only wider environment is other homes in the clouds, partly representing the sidelining of nature that we have now. Would one desire that? In CS Lewis's story on a magical Venus that he called Perelandra, desire leads from simplicity and innocence to horror and to victorious peace, with the feathers being torn off hundreds of birds to make the innocent Perelandrian woman more beautiful with a feather coat, and then to victory over the goals of the coat's maker. Perelandra is the name Machaelle Wright gave to her garden where she started researching our co-creative relationship with nature through her communication with nature. Behaving as if the God in all Life Mattered is her initial book about the co-creative relationship we have with intelligent nature. These are concrete expressions of the flow of desire, and paths to healing damage.

Desire was a token of value in the making of the projects we undertook at the GSAPP as students. The then recent Deconstructivist Architects exit at MOMA, and people representing that cultural impulse populating the school at the time, had a big influence on that. Desire represented all that we young architects … desired.

Building the profession and our relationship with nature includes our desire/s; either with desire or in an after–desire condition. This article focuses on the role desire plays as part of thought in the profession in this context.

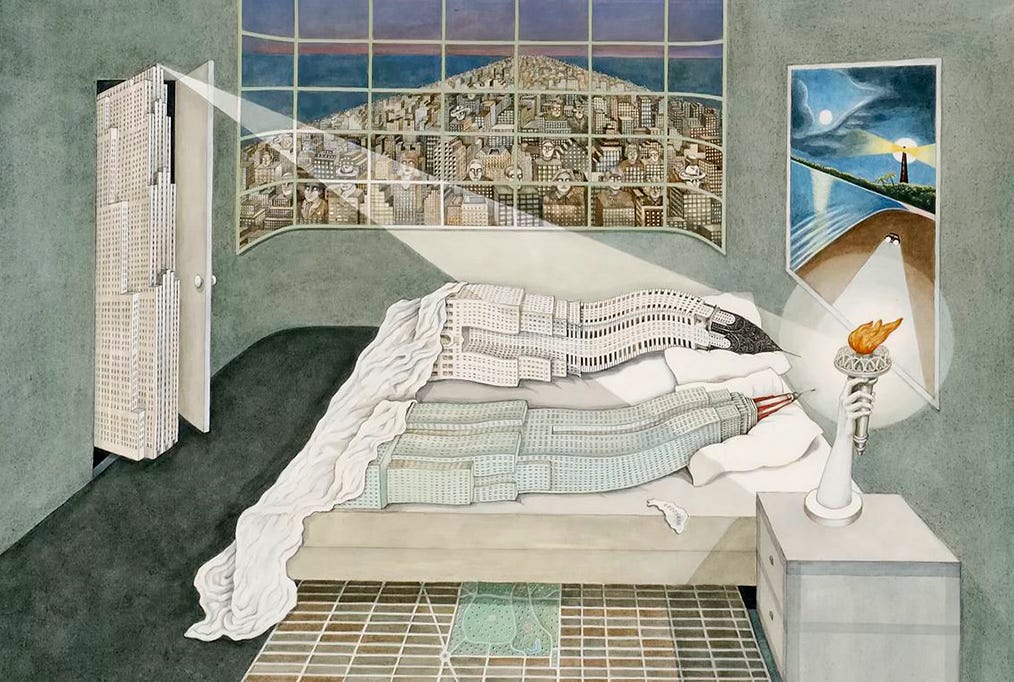

One kind of desire is exemplified in a narrative with architectural characters. This part of the original cover image of Rem Koolhaas' Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan. It is named 'Flagrant Délit', painted by Madelon Vriesendorp. The cover was originally uncredited, which to me represents the delirious desire of grasping at power of some of us.

Desire is a prominent component of architectural practice and in the education of architects. It is less central than it was. But books continue to be written about desire, and conferences on that theme are arranged.1 Desire holds qualitative value. Design is made to respond to the desire of the client and the occupants and participants while the architect fulfills her desire for form with a range of spaces and objects between functionality and ‘eye candy’. In practice, desire is a programmatic element of a project's Entwurft that appropriates the client’s intentions that the architect prepares.

Value of dwelling is generally expressed in terms of convenience and luxury, formed as physical quality that serves desire, primarily through architecture’s technicst proxy. The colour of the car in the advertisement is chosen with desire in mind. Desire also serves as a ‘wild card’ in the mutual play of the client and the prerogative of the practicing architect to allow for the intensive technical requirements of building, which include finance and regulations, where we manipulate needs and the variety of outlooks, and transform it all into requirements that lead to architecture. Desire allows ‘requirements’ to escape the strictly pragmatic terms of technology and materiality, and it allows for serving individualistic ends, personal ends, and implies satisfaction and satiation. Desire in this role in concealing conflict within those terms of the profession, even as it enables the practicing architect’s functionality.

By asserting desire as a form of need, real-estate, commercial and consumer product market demands become a need of business and economy that architectural professional practice then provides for. Desire has come to be a programmatic attribute, that is often codified and programmed into projects as a positive idea. The architectural profession explains this as value-adding objects of desire.

Schools of architecture define their curriculum with technical accreditation and qualifying requirements. But a way to raise up architctural projects with a valuative components is through desire. We otherwise often shy away from humane need beyond the technical attributes. Desire is not really humane, but it points toward human qualities better than mere technic. This is a concealed conflict. Desire-as-programme absorbs need related to the difference between occupying functional spaces, dwelling and what is nature or natural. We want to harmonize with nature, including our inner nature, without co-creating. We cannot avoid that we are always actually co-creating, but the systems of the Machine Age Modernist profession ignore it, and we are not listening.

Desire is an architectural programme conceived as additional to what is available to provide for feelings of fulfillment and proper actions through the means of building or otherwise preparing an intentional environment. Desire is part of architectural discourse as a spark of interest that gives the intended environment the liveliness of a well made product, but it also serves to value the cost of architectural preparation as ‘additional’. The need for aspiration and love is re–territorialized as desire in technicist architectural practice to allow it to be joined to the fulfillment of the experience of dwelling that architecture fulfills.

Desire as a programme allows the architect as the operator of the preparations of dwelling to bring the entire spectrum of world into the realm of their role and yet to be free choose their desire, embedding it in technical design services. There is nothing necessarily wrong with this, but the process of it necessarily causes issues. The practice of architecture and the individual architect who is practicing architecture may pre-load the essential quality of need-as-desire into their projects, where ‘need’ is then de-fanged and has the quality of being ‘optional’ in the sense that desire retains the quality of choice, turning to the freedom to choose, which is human. This is what backfires in practice. Architecture is felt as optional when it is about desire. Architecture is de-valued vis a vis concrete or material technological and procedural values (including finance and economic elements), reenforcing the issue that desire as programme seeks to circumvent, de-valuing architecture as a response to our need for wellbeing.

It is a reversal in responsibility for professionals' authority. What is desired as just reward stands for the right of freedom-of-choice that forms our choosing. Freedom-of choice is a human capacity, which is fundamental to human being, generates the need for responsibility using that capacity. Elevating desire as a necessity that poses as a right doubles what is already a natural attribute of consciousness, leaving its original nature undone. Desire as pragmatic functionality to prepare environments is in conflict with architectural presencing in practice through human capacity for intentionality and will. Such programming of desire, as a shift of quality to capital value via technology, must contradict architecture’s essence.

This is more than ignoring nature's role in our lives. The professional seeks to negotiate and becomes an aggressor in that conflict. Desire undermines the value of the profession in light of humanity and our role in nature. This is a feedback loop of affect, symptom and cause. The architect is in an essential conflict of interest with her architectural outcomes. We have the weirdly frozen unnatural world of the Jetsons.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Office for Presencing Architecture to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.