What value makes not-architecture impossible?

P-01.1 Going beyond meaningfulness to presencing architecture in practice. Part 1.

A story at my beginnings in architecture can express a discovery of humanity, and my humanity, that showed me what I need and what is needed. Discovering humanity in me and in others mixed up with practice. In that space, my personal path is linked to the value of the architect's work. The production of architecture is bound up with who we are and how we do it. Methodology in practice integrated with what a project for architecture is intended to provide. I feel that I can rope in what this means with a few more letters here on Substack, down the line.

The story begins when I first came across the space of architecture. In high school I was able to do both drafting courses for grades 11 and 12 with a perfect score in only about 4 weeks for each course. That left about 3 months with nothing for me to do. In the grade 12 iteration, the teacher decided to give me something further to do rather than have me sit in class with no work, as I did in the first semester.

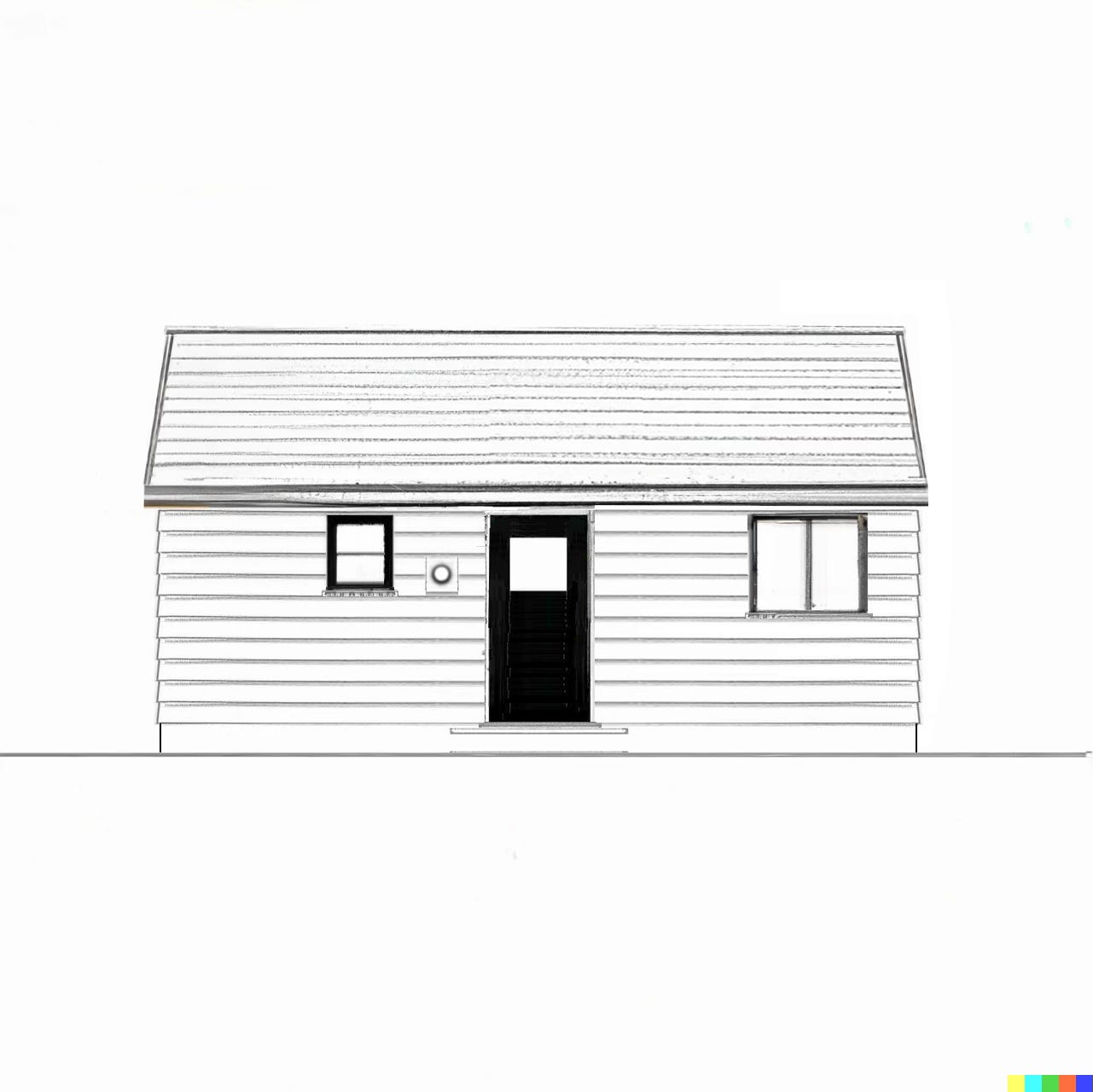

He gave me one elevation of a small house. It was a house for an 'Indian Reservation', he said. My task was to draw a floor plan and the other 3 elevations based on this one 'front' elevation drawing. This would have meant moving from drawing orthographic, isometric and perspective mechanical drawings to drawing buildings, and this assignment included design. I had to invent and create parts that were not already messaging formally through the information that I was given. This moment introduced my career to me. But the field of the profession was not clear to me, nor its importance for a long time yet.

I asked Dall E 2 to generate a sketch of how it was. It's somewhat photoshopped to better approximate what I was given then. My reaction was that it was a horrible little building that no one would actually want to live in. The elevation had no quality. The big window was awkwardly placed and not well proportioned. The window to the left of the door with the electric meter between them seemed to me a very ugly for the entrance to a home.

To interpolate that elevation would include its denial of valuable qualities. Of course, I could have also re–designed it to my liking. As the 16 year old who did not know about the profession of architecture, this did not enter my mind. I loved developing views of machine parts from limited information, like a puzzle. I loved making the pencil line perfect. My parents had inculcated in me a post-WWII concept of living to survive and being happy without luxury. Luxury appeared to mean having no proactive choices about living space. My thinking did not have the freedom to say that this can be beautiful using the very same materials and details, dependent on what I chose to design and draw to make it so.

Interpreting that building would be a mess of connotations. How can such the desperate reduction of life quality as reflected in that little cabin be justified? How is it that there are people who can draw things like that, having the skills and taking life–time, not get bored and demoralized? How can whoever made that be so robotic or heartless? I pondered some of this. I felt poverty. That elevation expressed desperation to me. It could be my own desperation. I could feel in that elevation with its lack of joy and charity, and the long path through my ignorance. I did feel a nightmare shadowing into my life through that drawing.

I felt that it was a waste of time to deal with the assignment in terms of that uninspired junk. I felt a lack of meaningful ground with which to fix that design. But it did shift my thinking to the wider space of design and I thought like an architect. Thinking like an architect, a struggle with the way our environment speaks of much abasement of human capacity and the disregard we have for each other and nature came up.

The notorious (but also celebrated) 'Vancouver Special' was coming up everywhere in the GVRD at the time. That bottom lining defaulted built volume, decorated on the front like a smeared up too friendly drunk neighbour at a neighbourhood party, was coming up all over. This house type and many since, including most of the McMansions, are made in the same socio–cultural frame as the small house above. How does the need to express efficiency become poverty? Most of the environment around Vancouver was marked with buildings that reflected this, allowing it to form the public environment. What value is needed to make such things impossible?

From the article 'Vancouver Specials'. https://blogs.ubc.ca/vancouverspecialsimmigration/files/2015/12/1200_vancouver_specials.jpg

After 2 years of training at BCIT, working as an architectural technician I got very fast at producing construction documents. I worked for a couple dozen architects and builders cranking out their documents for their deadlines. I experienced no effort to collaborate with the users nor any discussion on architectural values during this period. A few years later, encouraged by the Vancouver architect I finally settled on working for, I landed at the University of Oregon's AAA and discovered process-based practice. Here were professors who based architecture in choosing values and ethics.

An undergraduate architecture program emphasises competence in professional practice. With 5 years of production behind me, all that was clear. My goals, such as they were, could be surfed on the basic requirements for project work. The freedom to create meaning in projects and how to put it there was pulling me forward. I discovered the need to increase my capacity to discriminate between the means of building, process to develop the planning for architecture, the expression of life in doing this, and the specific people and tasks that provide the opportunity to do that 'here', 'now' and this particular way. At first I was able to turn the question, 'Why would I do this?' to 'What is the meaning of this?' Concepts appeared like magic from the project needs put before me. But the demand to define the designs concretely with value engineering and decision–making models was crushing. The conflict between architectural and scientific technological design ignited. Meaningfulness and connectivity with what is right remained the still middle. An inscrutably deep problem glimmered and brought me hope of a way through.

The professors propagated the answers of architects Louis I. Kahn and Christopher Alexander, who were the chalk and cheese that formed the poles at Oregon at that time. The references by which work was justified looked back on Modernism, but not its history. Complexity and Contradiction was present, and Post-Modernism went as far as A Pattern Language and American 'classicist' Post-Modernism and architecture such as by Leon Krier, Michael Graves, early Robert Stern, Charles Moore and Aldo Rossi. Examples such as the Linz Café, ancient Rome's urban form, Sea Ranch, Piazza d'Italia were bandied about. But also, Modernist examples such as Aldo Van Eyck, Lever House and the Seagram Building. Louis Kahn's legacy was just completed then and we knew about his projects through the direct experience with Kahn of some of the professors there at the time.

There was something in great architectural work that I felt, but could not yet distill. Two rooftop remodeling projects come to mind to express the riddle of this potential. Paul Rudolph's own home in Manhattan and Coop Himmelb(l)au's Rooftop Remodelling in Vienna. Paul Rudolph's work reflects Modern Machine Ages technological thinking, apparently, while CHB(L)'s does not, although it does. Both are built on the past. Both rooftop remodels have the characteristic of providing for architecture in a way the reforms the 'rules'. They are only an inspiration, a point to launch from. They do not near the future at all. They are on two sides of a line that we are still near. Rudoph's architecture prioritizes Machine Ages technological value as a meaning bearer for its architecture. The other does not. Typically these differences are taken as stylistic and, given that they are elite projects, considered irrelevant to the general world. But a deeper difference is clear in them, a transition that has not been extended into how we can prepare the environments that we need to support the advancement and evolution of our humanity.

Left side top and bottom. From 'Modernist Architect Paul Rudolph’s Manhattan Townhouse Hits the Market' https://galeriemagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/0131085314-768x1449.jpg

Right side top and bottom. Rooftop Remodelling Falkestrasse Wien.

Exterior. https://www.archilovers.com/projects/69384/rooftop-remodelling-falkestrasse.html

Interior: https://divisare.com/projects/305869-coop-himmelb-l-au-wolf-d-prix-partner-rooftop-remodeling-falkestrasse-wien

At Columbia's GSAPP in 1989 when I arrived, the focus was Deconstructivism. It was reviled by many people. It was a kind of nerd-punk (some say that it is rock and roll), that embraced the absurd and hubris, and attempted philosophical grounds. I prefer the terms 'classicist' and 'abstract' Post-Modernism, and to expel the philosophical aspect as an internal organ. This work was based in the knowledge that Modernist and Machine Ages culture needed new grounds to move forward. It had to oppose a lot of power that asserted the status quo, taking on a dismissive tone, while the voices came out of privileged wealthy places, with functioning infrastructure and questioning access to food and shelter was not present.

Star power and the hubristic clamour in the press of the last magazine (pre-internet) generation and the attempt to connect to build a legacy philosophically largely failed and drowned out the more profound value of the work, ironically. Even Philip Johnson's essay for his Deconstructivist architecture show at MOMA does not properly explain the inherent values of change in it. The cultural content of Post-Modernism, its values and the neoliberal messages, turn out not to be the most important aspect for the practice of making environments that presence architecture. While technology for contemporary building is widely spread into cultures beyond those wealthy centres now, those values have not translated much into cultures that sincerely need material betterment. I saw general incomprehension of Post-Modernism’s generative values in India. Critical Regionalism and a variety of regionalist thinking have propagated, keeping the sincerity of Modernism at large.

Architectural value that allows us to evolve beyond the devolved Modernist concepts of efficiency, science and minimalism that are opportunistically taken for profit, such as with the Vancouver Special and 'minimalist' housing, malls and office buildings etc. all over the world, have been largely subverted. Saving resources is a mantra, but it not stopped and often results in massive waste and destruction. But the professional focus on technology has devolved to focus on building, with the idea that efficiency is humane. Efficiency has not brought us the care for each other and the environment that we need. The new efficiency is zero carbon, zero energy and other such climate orientated measurable reductions. Changing the content of what is efficiently handled is triage, which is needed for sure.

Architects formed the way we build now, and there is no other to express values to change that. Where values that we make environments for, which is the human role in the world, interacts with the process to provide them is the most salient point of change. The key element is architecture, not building. What works is to add humane values and controlling the importance of technology. If we experiment with the ‘how’ of that as the same as the ‘what’, then it touches what was begun in some Post-modernist architecture.