Circumnavigation of Downtown Conventional Tour of Vancouver

CS-02.1 The RAIC'24 Conference tour that delivered on the world beyond city streets.

We walked around the downtown on the tour. The tour was to experience the issues we found in the conference in the context of Vancouver. In this Substack I am writing about my take on the Conference, especially the presentations that had the word ‘future’ in the title.

Vancouver has a lot of interesting and globally relevant buildings, and certain elements of the city and its planning have at certain times been exemplary in a positive light. If all of the Conference tours look at these, we can have a single tour that looks at the wider context. The Biosphere and Spirit of the Place where people live in the traditional Skwxwmú7mesh territory at a Squat called Vancouver no longer feels like a radical name for this tour. We want to avoid getting caught up in the shiny city that marginalizes issues of colonization and the destruction of the biosphere. It was not difficult to proceed with an attitude. Walking as experience very much overshadows intellectual talk. The essence of the walk was to experience, to feel and to learn, what this place where Vancouver occurs is, despite the Colonialist Financialized Machine Ages City, by passing through it to places that retain interface with the spirit of this place.

There is a clear difference in what we may feel Vancouver to be when experiencing the water, sky and forest of the biosphere all around it, remembering that it was continuous throughout the entire territory that the GVRD occupies. The difference is, in fact, stark. It was easy to sense this, especially at the rather dramatic reveal of English Bay/Salish Sea when crossing under the Burrard Street Bridge. We all seemed to feel the moment of entering into the 'other' from Vancouver's urban city structure at False Creek as we passed under the Burrard Street Bridge, suddenly arriving at the threshold to the Salish Sea. This moment was the gateway to the walk; leaving behind the 'inside' of the city, which is so different from its context.

That difference is also the difference between the profession’s process, and what it needs to move toward. The density of False Creek development, which was intensified by discussing the future water level flooding all of Granville Island and much more, and the proposed measured retreat of the False Creek community along its south shore, (referencing the presentation "Be the Solution, not the Problem" What can the Future hold for False Creek South?) was left behind.

Walking all along the beaches toward Stanley Park, there was a unique pull to the horizon, to the islands and mountains, and to the sky. It felt of freedom and freshness. The expanse and the distance balanced the weight of the city behind us. This was a real partnership with the environment. The sand and waves, and the wind in our faces, spoke to us of the life of the world here.

The eye of a settlement called Vancouver meets the spirit of the place here along this western shore. This is what Vancouver needs to be about, if it is to be large, as it is, and covers everything around here. There are many locations like this one along this shore to try.

At the Parks Board Office building we turned away from the Salish Sea to pass around the edge of Stanley Park. When we re–entered city-urban congestion on the edge of Burrard Inlet, after passing under West Georgia the connection with the land was gone. The group felt the difference. After the Burrard Street Bridge we had felt energized, and here it was a subtle but real let-down.

At the intensively built–up north shore of the downtown, we faced a complex array of urban design intentions. The north shore has heavily used urban promenades that have no native shoreline ground or growth. What appears as water on the map is to the observer at that edge a vast sea of boats in marinas, segueing into a flotilla of float planes and then two huge convention centres with cruise ships moored alongside. Beyond that, a container facility juts out into the water. Nestled between, on engineered edges of riprap and train tracks, are a heliport and the Seabus terminal. It is firmly of the ethos of erasing the local spirit of the land and water. Looking across the Burrard Inlet we see more industrial development and buildings with settlements seeping up the hill as if by capillary actions. The mountains seem remote over that barrier of disconnecting development.

This is not another bonding with the ocean and the biosphere. As much as a discussion of the biosphere and places like x̱wáýx̱way were intended, the intensity of the development caused us to walk silently. It was actually quite noisy. Points made about the ecotone with urban city space and relationships to earlier Indigenous settlements felt weakened. This is an urban leg, blending with the streets of downtown. When we re-entered the city, where we expect to be in city, understanding and feeling the metabolism and spirit of the world diminished further and confusion ended. We reverted to our normal steely selves, walking to our destination.

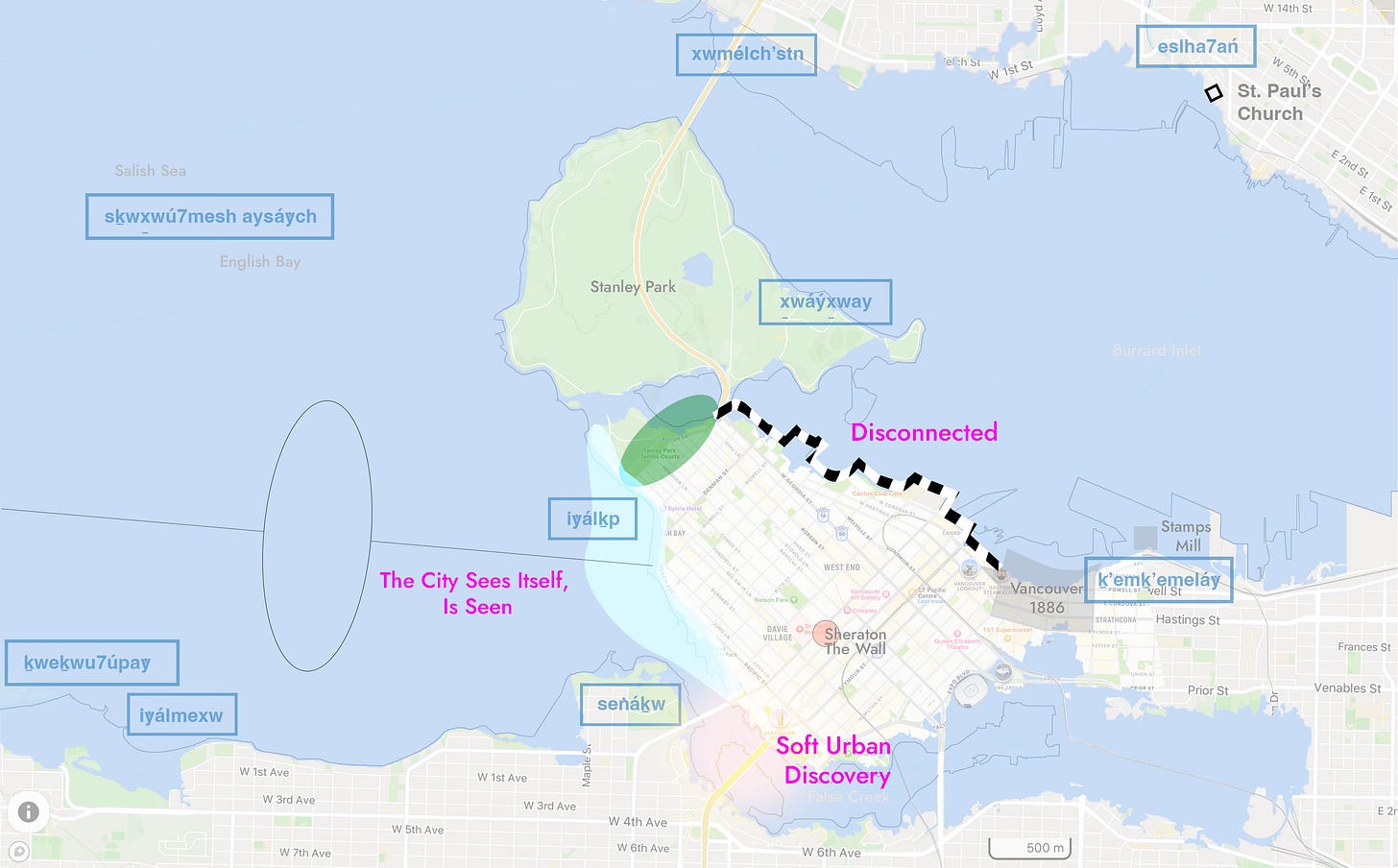

The tour route was clockwise from the Sheraton via False Creek and along English Bay. This map incorporates the City of Vancouver's own estimate of flooding yet to come in this century.

Some of the presentations of the RAIC 2024 Conference reflect these conditions. Like the conference, the city is considered to be contemporary. We can question its success, given the inequity of colonialism and housing poverty, as well as the climate and the destruction of the biosphere. We are struggling with what to do about the future that will assuredly bring great change. There were a number of presentations that had the word 'future' in their title. But none of these actually spoke of the future. I visited all of them.

Discussions on increasing profitability and entrepreneurialism are not futuristic if they are not underpinned by discussions of proposals, research and seeking–in–practice, and education for what value architects provide and might bring. Despite CASA–ACÉA's very professional multidirectional approach, none of their effort actually addresses the future of architecture either. New graduates will influence the future of the profession nominally, but being future orientated means questioning what the seats that they fill are for. There is an essential difference between being a new participant and providing something 'new'.

The presentation New Models of Practice about the University of Calgary’s DDes program was the most future orientated presentation that I was to see. Two experienced architects presented their doctoral research exploration of needs that they found in practice. Darryl Condon sought to extend practice to services preceding and post- the current frame of commodified architectural service. Barry Johns' research is on removing the cost of property for infill housing as part of the service in architectural projects. It is a form of activism and community development. These will influence how architecture is practiced in the future and the value that architects bring. These will give entrepreneurialism in practice the fuel needed for generating value and increasing that value as prosperity – a term that David Fortin offered to replace 'profit' during his comments in the earlier Future of the Profession Panel Discussion.

We can see two areas of discussing the future of architecture. One is toward doubling down on the profession's formats and systems, trying to streamline and further commodify and package good ideas, following commercial and business practices. The same question for Vancouver is if building even more higher towers and densifying will solve any issues, if to date we have grossly unaffordable and inadequate housing that is trending toward even worse poverty.

The other approach to the future addresses the essential misfit or misalignment of the profession and our cultures with architecture and its value. This is about foundational aspects of human(e) life and nature. Questioning this should not be a surprise. There has been no change in this since I first encountered the profession in 1981. The pressure on the profession has only increased. We can feel that on our walk. I like to think of it as parallel to the pressure on climate the biosphere and the difference between our action and equitable resolution and peace.

Many of us can feel the gap between the architectural profession that seeks competence through the building buildings, and competence through providing architecture and wellbeing. Filling this gap is an optimistic area for professionals' 'upside' – meaning prosperity through finance, society, community and invention. It involves redefining the profession's value and of change to realize that value. It is very much a business concern. It bears on the questioning we did 150 years ago as the First Machine Age came to life, asking what the 'new' form of architecture needs to be. We need to ask that question again now.

The essential fact is that all human beings are always somewhere. This is an essential fact of being that is akin to food. Unlike food, environments can not only starve us with empty calories, they can actually tap us for our energy or waste our energy and our life time and, like food, can poison us. Do our environments nourish us? How do they support human being? Do they support our consciousness and its inherent aspiration? Is it still architecture if buildings do not serve this, not to mention if they are making us ill or killing us? Detoxifying building materials and air is not the issue I am referring to. Is being housed enough? Housing is a zero sum function. Homes are non-zero sum and multipliers of value.

Do people have right to architecture? If we even have trouble with the right to have homes when everyone needs one, how far we are from architecture!

Most importantly for a discussion of the future of the profession is the question of knowing what architecture is. In general, we seem to be afraid of this question. How do we allow professionals to exist at their level of understanding while realizing and responding to that the majority of so-called architecture is not? The lack of architecture has been devastating to the profession and wellbeing of architects. How do we bring the value of architecture to wider social and cultural valuation when that is difficult even among professionals? It is neither a fixed nominal definition, nor science or philosophy. We may define this question as we wish, and we need to start.

The call for graduating architects to be better prepared for work in the office can be countered and balanced by the assertion that the profession survives because of the provision of the widest parameters in architectural education. In lieu of a clear social and cultural place, we have at least kept this open. Graduates bring the wider scope of architectural value that is then brought to bear in specific projects and scopes of businesses and studios.

The period in which the new intern architect comes to function in one of these contexts can be frustrating, but every architect should be glad for it. This is one of the fundamental value adding attributes that we have. It contradicts commodification and financialization, creating openings for new pathways. It may frustrate certain business orientated architects or corporations because it is a drain on the short and medium term balances. But the profession's value at all is dependent on new architects. This resource is squandered daily.

I had a discussion with a senior architect the other day who said that no firm should have to open their books to an intern. How ironic is it that so many architects wonder how little graduates know about running a business, yet by my own experience, verified by that moment of indignation at exposing books to anyone, if managers and owners are loathe in general to show these young architects how their business works (or does not work)? The call is actually that young architects should serve businesses; that is the actual issue. But the call needs to be for the responsibility to bring forth their capacity by serving the future through them, serving them to be/come architects.

Businesses in general tend to commodify and financialize all that they do and human life contradicts that. Obviously, we need to make money to support the work that we do. Architecture is not buildings, while building still defines the professional business life and functionality. This conflict is the reason students are not ready to work in most cases. No, architectural education does not support business. Instead: Is the business viable so that it can support providing architecture?

We have seen great devaluing of architecture and relative shrinking of the profession's reach over many decades. What must architects provide beyond buildings to change their value production to what makes architects more valuable? The answer is not as simple as the reductivist business orientated players like.

The issue of architecture that is always present and almost completely unspoken is awake here in the environmental division that we experienced as we walked. The schism between the natural environment and the space of the city, cut off. As we 'walk' through most offices of the profession and work in the space of project, contracts and business needs, are we cut off from architecture? Does a day of working for the wellbeing of the environment leave us saddened by the need to now fulfill requirements of technology and regulations? It can be exhilarating to facilitate 'design' and realize a project. Although it is possible to harmonize with technology and systems, it is not natural fit and never equitable to Nature. It is exciting to consider the vast field of potential that lies fallow here.

The questioning for this is: Why does this city need to so utterly reject the spirit of the place, its biosphere and its nature? Why must the biosphere and other cultures be erased where Machine Age Cities take over the land? Can the profession be more closely allied with human aspiration? How can architects harmonize and utilize that spirit, which is essentially love, to prepare architecture more truthfully and more fully?

What remains of the 1880s origins of the city in front of some recent towers at the north-facing shore on Burrard Inlet. Heliport on the left, Seabus terminal on the right. The old town at East Hastings and environs facing north into the Burrard Inlet has never been able to meet the spirit of place with poise. It is rotten; it is not where pride, community and spirit are at home. It is not a proud centre. Because of this, Vancouver is a carpet of urban structure about nothing.

When we walked around Vancouver, we discussed the inequity of the colonial city, that the original core of Vancouver has been sick for half a century, and that the whole of the city has created no basic moral right to occupy this land. We also notice that the city is not properly orientated in its place and so it is undefined urban design, architecturally. Any of dozens of intersections like Granville and West Georgia can be its centre.

Can it be that the profession as we know it, originally coming from the same cultural roots as the colonialism that formed Vancouver, has the same culture of inequity? Beyond its structure to organize and promote competent architectural services, does our architectural profession have the same pre-Machine Age DNA? Yes. This inequity and essential inhumanity is baked in. It devalues architecture for the commercial worth of real estate, of building built space and orientation to capital extracting value from (or adding to?) the public sphere.

Why do businesses not need lots of architects, and are happy to have creative aspiring highly educated underpaid graduates manning work stations where they have little guidance and no architectural role? We heard discussions during RAIC 2024 Conference that graduates are not able to engage properly in the business of architecture when they graduate. Answering discussions would question business that do not require more architects in powerful roles for making better environments and support of roles that will give stronger meaning to the presence of architecture. There is much we can do about this.

The walk back to the Sheraton Wall is uphill.